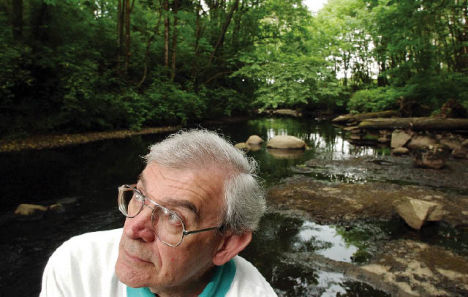

Walter Walker, a mentor for many in the Sapperton Fish and Game Club, spent most of his 85-year life living beside the Brunette River. Now deceased, Walker told other members about the thousands of salmon that once filled the creek each fall.

“He told me when he was a boy his mother would tell him to go down to the river and get a fish for dinner. That’s how plentiful they were,” said Elmer Rudolph, a long-time member of the club.

Rudolph knows the stories about when the Brunette was pristine and fish plentiful. He can also tell you about when it became a dead waterway.

It was 1955.

No spawning salmon made it that year to the Cariboo Dam where the river enters Burnaby Lake. Polluting industry in the Braid area killed off the spawning runs. Chemicals leached from a plywood plant, a slaughterhouse flushed its refuse in the river and a distillery piped hot liquid into it 24 hours a day, said Rudolph.

The same was happening along Still Creek, which flows through Vancouver and Burnaby and feeds Burnaby Lake and the Brunette. Industry also used the river as a dumping ground.

“The fish were getting it at the bottom and the top,” he said.

And everywhere in between too. Sewer outflows from businesses and homes along its course would empty in the Brunette.

“Complaints of nuisance created in Brunette Creek by it being used as a sewer by the Distillery, Frye’s Stock Feeding Yards and Swift’s Abattoir. Laminated Materials operates a dam in area and both the Provincial Health Officer and Provincial Chief Sanitary Officer suggest several solutions including filling the swampy area with Fraser River silt, a covered surface drain coupling the distillery, Stock Yards and Abattoir and running to the Fraser and flushing the Brunette regularly with the tide.”

– Minutes from the City of

New Westminster council, June 10, 1929

While industry is no longer allowed to pump effluent into the urban waterway, there is still pressure on it.

An estimated 200,000 people now live in the Brunette River watershed. It covers 73 square kilometres of highly urbanized area. Portions of Vancouver, Burnaby, New Westminster, Coquitlam and Port Moody lie within the watershed.

It flows from extinct creeks near Central Park, now entombed in underground culverts. The water then makes its way through the Still Creek corridor, Burnaby Lake and the Brunette River, eventually emptying into the Fraser River. Its waters also come off Burnaby Mountain and from numerous parks, neighbourhoods, industrial areas via creeks and storm water drains.

Two major highways criss-cross the watershed. At least eight bridges cross over the river, including Highway #1. Large shopping malls and acres and acres of asphalt roadway and parking lots have been built within it.

There are more than 200 kilometres of waterways in the watershed. Some streams have been lost, such as Lost Creek. While others have been paved over, culverted, diverted or used as sanitary and drainage ditches during the last hundred years of development.

Despite all of this, fish live in the Brunette and the many tributaries within the watershed, such as Stoney, Eagle and Silver creeks. Patient streamkeepers, who measure their success over five and 10 year spans, say the watershed is improving.

They’ll also tell you the next few years for the river, especially in its lower reach, are critical. Restoration work done by streamkeepers, local government and others in the most polluted portion of the river during the next two years would make the urban waterway’s comeback one to marvel at.

Children may no longer be able to go down to the river to net dinner for their mothers but each fall they can watch salmon spawn.

That, says Rudolph, is making the Brunette a success story.

“We travelled against the current of the Fraser for about a mile to discover the entrance of Brunette Creek, as the brunette River mouth was effectively blocked by logs. We saw much local game and were paced by sea otters.

“We passed into the mouth of the creek and followed the right hand channel into Brunette River proper. It was very brown and very meandering.”

– Lieut. G.L Blake, Royal Marines, who canoed up the river around April 27, 1859.

Despite the historical and current abuse of the river, it still supports an abundance of life. Cutthroat and steelhead trout and Coho, pink, chum and chinook salmon spawn and live in it.

Canoe the length of it and you could spot great blue herons, kingfisher, osprey, a few eagles, beavers, mink, deer and other wildlife.

Mark Angelo and Bob Gunn have paddled the Brunette twice. Angelo, an international river conservationist and head of B.C. Institute of Technology’s Fish, Wildlife and Recreation Program, and co-worker Gunn see great potential in the urban waterway.

“You travel along the stream and you can see a lot of the history of New West and Burnaby in it – the industrial development that has taken place along side it over the last 100 years,” said Angelo, eyeing the leftover industrial remnants found at the edge of the river.

“You paddle down this river and I think it’s a source of encouragement. You think back to what it was 100 years ago, you look at what happened to it in the ’50s and ’60s. And now we’re seeing a rebirth.”

On a recent trip down the Brunette, they talked about how cities, industry, streamkeepers and the public must work together to make the river friendlier to fish and people.

“In the past we saw lots of this where the development took place right up to the banks of the river. I would like to think in the future we would do things differently,” said Angelo as the canoe floats past a warehouse that looms over the river. “In the future there may be ways to reclaim some of this riparian habitat. Under certain circumstances we could turn this back into natural riparian area.”

“We took enough provisions for four days and started with a lovely day before us. It was hard work getting up the stream which was very strong against us, deep brown coloured water rushing along as usual between banks most beautifully wooded. The debris of whole woods lying scattered across and on each bank. I suggested the name of the “Brunette” for the river which was instantly adopted.”

– Robert Burnaby, part of the first European expedition to travel up the Brunette to Burnaby Lake. March 20, 1859.

The Brunette gets its name from its colour. Water entering the Brunette from Burnaby Lake has a light tea-coloured tint. That’s because the lake is part of an ancient peat bog. Brown algae on the river’s bottom gives the water its dark brown colour.

As Angelo and Gunn paddle around a bend they disturb a blue heron fishing for its next meal. In stark contrast, they also have to maneuver the canoe around a steel cable and large concrete block – left behind by industry.

The river is very much a river of contrasts, says Angelo.

“You have areas in the upper section that are quite natural and quiet, then you have areas like this where you hear sounds of an industrial nature,” he said. “You’ll go through sections where there’s a lot of streamside habitat and its green and natural. But then you go through other stretches down river where it’s very industrial.

“It is very much a river of contrasts.”

Despite having industrial development surrounding the lower reaches, volunteer streamkeepers continue to battle for the river’s environmental survival. Often, said Rudolph, “It’s two steps forward and one step back.”

For example, there was good news and bad news when streamkeepers compiled last fall’s spawning counts. Just 56 adult coho returned to spawn, a decline seen throughout lower Fraser River tributaries.

Sea run cutthroat trout were also down from previous years with just six recorded by streamkeepers. The Brunette’s steelhead population continues to drop and is estimated at 50.

The good news was the number of returning chum and pink salmon. They counted 240 chum and 61 pink in the Brunette and its tributaries. The pink run is especially encouraging for streamkeepers, after trying to establish the salmon species for a number of years.

“We were getting the odd one one year, the odd few another year,” said Rudolph.

For more than 35 years, streamkeepers have carried out various projects, such as, building a salmon hatchery and creating a fishway over Cariboo Dam, allowing salmon to get from the Brunette River to Burnaby Lake. Other early work done has included stopping outflow pipes from discharging raw sewage into the river.

Most recently, the emphasis has been on creating fish-friendly habitat. Features such as weirs provide pools for returning spawners to rest in. Woody debris, such as stumps, are anchored to the river’s edge so fish can shelter underneath them in high water events. They also reduce stream erosion and increase the organic material.

Streamkeepers find themselves battling nature sometimes. An overpopulation of beavers in Burnaby Lake resulted in the rodents migrating down the river and destroying vital trees that provide shade and organic material. The river stewards protected trees against the marauding beavers by wrapping them with chicken wire.

“A cold clear starlight night, over us the dark foliage with a young moon silvering the whole, the Great Bear quite overhead, and every star clear as crystal. Nothing to break the stillness of the forest but the rippling of the river below us, the rustling of the breeze in the pine tops above, and the occasional note of a lonely owl somewhere near us.”

– Robert Burnaby, from the book Land of Promise. March 20, 1859.

A few hundred metres from where it enters the mighty Fraser River, the Brunette forks. The channel to the east, known as Brunette Creek, is a man-made diversion and a straight shot to the Fraser. The other fork is the historical channel, which takes the scenic, meandering route to the Fraser.

If you’re on a canoe or a raft, the diversion channel is your only choice. The Fraser River entrance to the historical channel is blocked by old log booms.

Angelo would like the booms removed so that more people can safely canoe it.

“The Brunette is a wonderful waterway in our community and these booms at the outlet degrades it,” he said. “The more people who spend time on a waterway, the more advocates are developed for the river. It engages more people, gets more people interested in the health of the waterway, and that can only be positive.”

There is great potential for the southern reach of the Brunette, said Gunn. The day may come when industrial operations move on and that’s when revitalization can occur. New provincial streamside protection legislation will create greater setback, allowing trees to once again grow alongside the river. There’s also the possibility land along the banks could become off-channel habitat – important areas for young salmon.

“We have to do a better job of integrating sustainable development down here. Maybe it’s time to consider that some of the industry around here is not appropriate,” said Gunn, referring to the Braid industrial area. “There’s a lot of potential here for restoration work.”

But a plan is required for that to happen.

“When a river has been damaged or impacted for decades, you can’t turn it around overnight,” said Angelo. “But the progress that’s been made in the last 20 years by stewardship groups, local government and regional government has been remarkable.

“My hope is, my belief is, that will continue. It’s certainly worth the effort because we’re very lucky to have a river like this that runs through our communities.”

“Over the last two decades, fish passage and habitat improvements by community groups and government agencies have brought back small numbers of spawning salmon to the Brunette watershed. However, for many possible reasons (including poor water quality), numbers of returning salmon remain disappointingly low.”

– Brunette Basin Watershed Plan, prepared by the Brunette Basin Task Group. February, 2001.

Before future restoration is done on the lower Brunette, it needs to be assessed. That will be carried out this year when core samples of the river’s sediment are taken as part of a Greater Vancouver Regional District study. Those samples may contain heavy metals such as lead, copper, zinc and manganese, left over from past polluters.

The study will also look at benthic invertebrates, bugs that live on the river’s bottom. The number and types of these bugs they find will tell scientists much about the water quality.

Once complete, streamkeepers want to see more water flowing through the historical channel and less through the diversion. Increased water flow will clean out the spawning beds in the historical channel.

The recent encouraging returns of chum and pink are prompting streamkeepers to now focus on the lower portion of the river. Chum and pink prefer to spawn in tidal areas of the river.

“We need to find out the conditions of the lower Brunette soon and do something about it,” said Rudolph. “We’ve been putting this off but it’s important we do something about it over the next two to three years.”

It’s not just streamkeepers and their partners that bring about the river’s revival, said Rudolph. The public also plays a crucial role. People living in the watershed are becoming aware of how their activities affect the river and its aquatic life.

“We’ve proven the only way you can bring an urban river back is public education. You can work your brains out, but unless you educate the public not to wash their cars on the streets and have soap suds go down the drain and not to pour paint down the storm drain, this watershed would not survive.

“The public, to a large degree, has bought in over the last 20 years. The only way they’re going to be able to bring their kids down here and see fish, is if they do their part.”

In the future, the comeback of the Brunette may be used as a blueprint for other streamkeepers and conservationists looking to do the same.

“We’ve proven that if you can do it here, with this river, you can do it anywhere.”